Has Spotify actually wrapped up the thriller of musical style? | Music

Move over Mariah Carey: as of late the arrival of Christmas is marked by the arrival of Spotify Wrapped. Since 2016, the streaming large has generated end-of-year listening statistics that declare to disclose customers’ most intimate music secrets and techniques. Infinite discourse about most-played songs, responsible pleasures and anticipated genres ensues. It’s a savvy advertising and marketing scheme for a platform that in any other case makes headlines for paying musicians poorly, though it appears few of us can resist the chance to point out off our exemplary decisions. However what can this knowledge actually inform us about our music tastes?

“People are good at looking for reflections of ourselves in something,” says anthropologist Nick Seaver. The writer of a brand new guide referred to as Computing Style, he argues that it’s vital for us to know “how that mirror acquired made, and what sorts of distortion goes into that reflection … It’s not simply displaying you as you might be. It’s formed by all types of choices that people who find themselves not you’re making.”

Larger than boring notions of so-called “good” and “unhealthy” style, our music tastes can really feel foundational to our very selves. A badge of belonging on the playground, the glue that holds collectively a friendship, the balm for a brutally unhealthy day, the music we hearken to is usually a coping mechanism, a time machine, or a imaginative and prescient of the long run. However why can we love what we love?

In Keep True, a vivid new memoir by New Yorker workers author Hua Hsu, music style is all encompassing. In Hsu’s 90s coming-of-age, music is the compass and the measure by which he judges these round him. He pinpoints how the correct track, in the correct second, can change all the pieces – and the way followers can discover divergent meanings throughout the identical choruses. Early within the memoir, Hsu is flicking by the crates at a file store together with his father, keenly concerned about the way in which their tastes converse to one another. “We had been enthralled by the identical music, however it confirmed us various things,” he writes. Teenage Hsu finds “liberation” in Slash’s solo on November Rain whereas his father hears the guitarist’s “virtuoso ability”, however their shared enthusiasm presents them a valuable level of connection.

However for anthropologists, style is much less of a romance than a science. “Folks usually take into consideration style as being actually particular person,” Seaver laughs apologetically. “However within the social sciences we are saying: ‘Ah, that’s probably not true.’ Your tastes are a part of a broader social patterning that extends past you.” He means that our typical understanding of style is formed by the phantasm of alternative, akin to going to the file store: “Amongst a set of obtainable picks, what file are you going to select?” Seaver asks me to hold out a thought experiment. “Think about, what wouldn’t it imply to have style in music earlier than there was audio recording?”

It’s flattering to think about style as a private alternative as a result of it encourages us to imagine in our personal individuality. Music applied sciences have lengthy capitalised on this, all whereas leveraging the emotional connection between a listener and a track. Forty years in the past, the Walkman gave rise to the “Walkman impact” – a time period for the way the moveable know-how allowed listeners to make use of personally curated music as a reality-shaping soundtrack. This 12 months, Spotify has a brand new tactic to influence us of our uniqueness: based mostly on their actions, customers are given one in all 16 new “Listening Personalities”, from the “Specialist” to the “Replayer” or the “Early Adopter”.

Spotify’s emphasis on individuality might be a technique to fight accusations that streaming platform algorithms – which plot data-led paths between songs and artists to make suggestions – are corrupting influences on their listeners, encouraging homogeneity, and due to this fact detrimental to lesser-known musicians. “Folks consider them not solely as being good” – as in efficient, says Seaver – “however that they are often so good that it’s unhealthy.” Dangerous, on this case, is the opportunity of residing in a sound bubble of your personal creation, unable to interrupt free.

You may nearly think about such a sound bubble interesting to the teenage Hsu, had been it not for the way a lot he prizes discovery. After first listening to Nirvana on late night time radio, he believes he had “occurred upon a secret earlier than everybody else”. His perception in himself as an explorer is essential to his idea of selecting the “proper” music, and he describes the snobbish tendencies of his school years with acute however sympathetic element. He writes that he “outlined who I used to be by what I rejected”, shaping himself by a puritanical method to sound and style that will really feel acquainted to many music followers.

The memoir balances the exhilaration and self-inflicted isolation that arises while you pledge allegiance to a sure style, and the way style might be each a declaration of distinction and an try to achieve membership to a selected tribe. It additionally reveals how style is a transferring goalpost: months after his “discovery”, Hsu is upset. “The day got here when far too many classmates had been carrying Nirvana shirts,” he writes. “How might everybody establish with the identical outsider?”

As markers of insider/outsider tastes, style works in another way at the moment. Over e-mail, Hsu displays that in contrast to within the 90s, “there’s now not a transparent monoculture to withstand”. Now {that a} wider vary of music is simpler to search out, at the moment’s listeners usually have fun breadth of style moderately than specificity: Spotify’s finish of 12 months knowledge even consists of stats on what number of distinct genres a consumer has listened to. Eclecticism is a advantage, with youthful music types like hyperpop and Ok-pop constructing on the curatorial impulse of sampling in hip-hop and creating self-referential, genre-agnostic sounds. However and not using a outlined sense of mainstream sound to defy, Hsu factors as an alternative to “monolithic platforms” because the powers that be.

Seaver’s work reveals how software program engineers, scouring knowledge for patterns, can spot listeners congregating round sounds, and title these teams accordingly. In 2018, Spotify “knowledge alchemist” Glenn McDonald described this as a surprisingly holistic follow: “Possibly they’re not precisely genres but,” he stated, “However I can title them and see in the event that they flip right into a factor.” (The a lot debated “Escape Room”, as an illustration, is an “in-jokey” style coined by McDonald to embody sounds as disparate as the luxurious alt-pop of Fragrance Genius and Tierra Whack’s surrealist hip-hop). When listeners are stunned to listen to of their affiliation to an unknown style, Seaver describes this as a possibility for them to “study one thing new about [their] style”, however it is usually indicative of those shifting centres of energy.

Artists and music journalists have been coining genres for many years, based mostly on sounds shared between artists. This new period for style is derived from listener knowledge and labelled by engineers who, Seaver says, by no means anticipated to grow to be authorities on the matter. This speaks to the contradiction on the coronary heart of Computing Tastes: it’s each simpler and tougher to pinpoint an individual’s music style than you may anticipate. All of it is dependent upon what you suppose style is. Spotify can inform us what number of instances we loop a favorite track, make cheap assumptions in regards to the genres that talk to us, and deduce from GPS knowledge what we’d need to hear within the fitness center versus the workplace. However Seaver stresses {that a} key anthropological query stays unwrapped: why do individuals love the songs that they do?

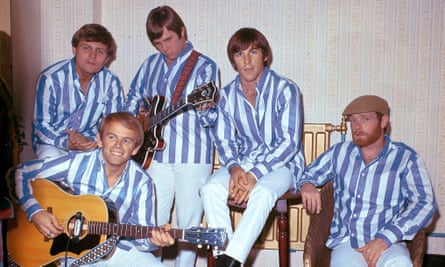

Hsu’s memoir holds some solutions. Keep True reveals music to be a continuing companion, capturing with transferring readability how our emotions in direction of a sure track can ebb and circulation over a lifetime. At school, Hsu is within the automobile together with his buddies, singing alongside to the Seaside Boys’ God Solely Is aware of. Of their throaty approximations of the Wilsons’ harmonies, he experiences a sudden sea change. “I lastly felt in my physique how music labored,” he writes. “A refrain of nonbelievers, channelling God.” In these two minutes and 55 seconds, he breaks free from his siloed idea of style and discovers the track anew, discovering in its harmonies an embodiment of togetherness. Later within the guide, after the stunning demise of his greatest good friend, he reaches for the phrases to explain precisely how the track has modified once more. It feels unsettling, he writes, as a result of “I heard all of the earlier instances I had heard it”.

Music lives with us. Greater than most different artwork varieties, it’s omnipresent. And though streaming companies may surreptitiously curate our listening experiences, Spotify can’t account for the songs that get caught in our heads. There isn’t a calculation that may completely clarify the knotted feeling of a once-loved track that holds too many recollections, nor the feeling of peculiar your self when a brand new sound takes a maintain of your coronary heart. Hsu places it greatest when he conceives of sharing songs as a gift-giving, writing: “The best individual persuades you to strive it, and you are feeling as if you’ve made two discoveries. One is that this factor isn’t so unhealthy. The opposite is a brand new confidant.”

Keep True is an exquisite tribute to how we use music to see ourselves, and to let different individuals perceive us. But it surely doesn’t shy from the bigger mechanics at work, both. Of Nirvana, Hsu displays that, on the time, he didn’t realise “different” was simply one other advertising and marketing software – however this doesn’t cancel out the band’s transformative impression on him, or undo the outstanding alternate of letters these songs impressed between himself and his father in Taiwan.

Surprisingly sufficient, Hsu’s memoir involves the same conclusion as Seaver’s algorithmic explorations. Style is at all times altering, from the way it works to the way it feels. And tiny, private shifts can form style on a far broader scale. “Idiosyncrasies can create new areas of which means or appreciation,” Hsu tells me. “Tradition progresses by individuals refusing accepted meanings.” The identical might be stated for the messy mixture of human habits, biases and assumptions which feed streaming platform algorithms. Spotify can present us a model of ourselves, however by no means the entire story. Whereas music developments will come and go, and new listening applied sciences rise and fall, it’s life that can at all times color sound.

Source link